Pembrokeshire is a popular destination for tourists. They are attracted by the unspoiled scenery, beautiful landscape and abundant wildlife. While some people relax on the fine sandy beaches, others seek adventure on land and sea.

They may kayak up the Daugleddau Estuary or go coasteering along the rugged coastline. Other visitors take pleasure from conquering the Pembrokeshire Coast Path National Trail or from seeing an elusive bird or animal.

Visitors are of great benefit to Pembrokeshire and tourism is an important part of the local economy. The money they spend can help protect and enhance the scenery and wildlife of the area, while jobs are created to cater for visitors’ needs.

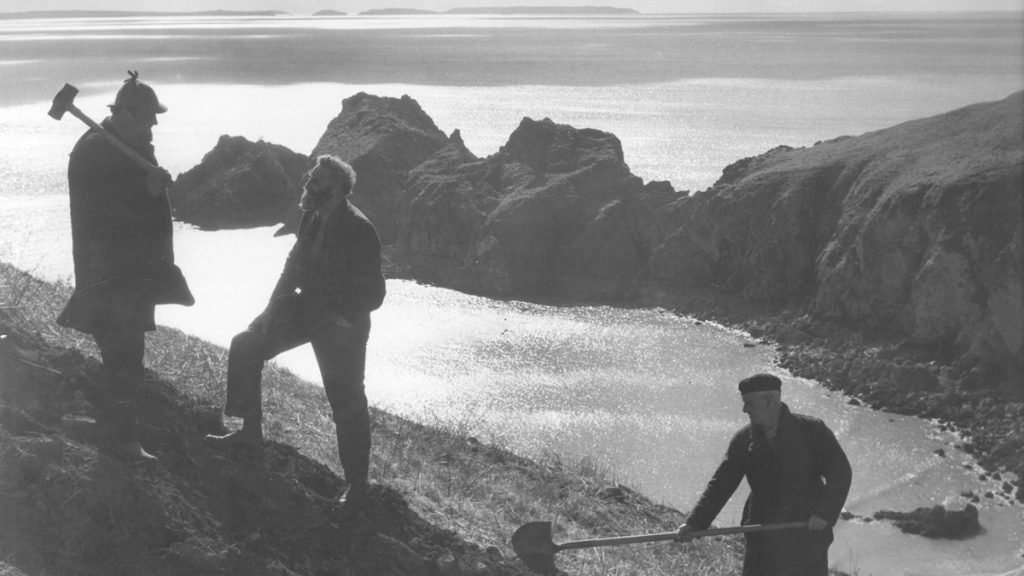

Coasteering at Porth Clais

Coasteering at Porth Clais

But while there are many benefits, tourism can also have negative impacts. Too many visitors in just a few honeypot locations can cause problems. Where do people park their cars? How do so many feet affect the wildlife and the Coast Path?

Caravan Sites

The Pembrokeshire Coast is a popular holiday area and so there is a demand for caravan and camp sites. These sites can bring economic benefits such as local employment to the area. However large areas of gleaming white and coloured caravans can spoil the natural beauty of the area, making it less attractive and less appealing to visitors. Some of the arguments given on both sides are listed below.

A caravan site in Pembrokeshire

A caravan site in Pembrokeshire

Advantages of caravan sites:

- Bring money into the area

- Provide local employment opportunities

- Provide low cost holidays for more people

- Take the pressure off local housing by providing alternative accommodation.

Disadvantages of caravan sites:

- Spoil the natural beauty of the area and make it less attractive as a tourist destination

- Employment opportunities tend to be low paid and seasonal

- People staying in caravan sites often bring their food with them and so do not spend much in local shops and restaurants

- Many of the access roads to the coast are narrow country lanes where touring caravans can cause serious traffic congestion

- The local infrastructure eg sewage facilities, has not been built to cope with the extra influx of people in the summer.

As there are already a large number of camp and caravan sites which are not used to their full capacity, together with the disadvantages listed above, the National Park Authority’s current policy is not to allow any new caravan sites.

Cars on Beaches

The general policy of the National Park Authority is that cars should not be allowed on beaches, as they may be a danger to bathers, children and others who may be relaxing and enjoying the beach. The cars themselves may also get stuck in soft sand, have to be towed out and suffer damage due to the saltwater and sand/pebbles. They can also cause damage to the structure of the beach, vegetation and marine life.

For every beach the foreshore owner and/or the local council is able to make byelaws to control what happens on that beach. In most cases cars are not allowed on the beach.

However, in a few cases, they are allowed onto the sand in order to launch boats from trailers – for example this happens at Broad Haven North and Freshwater East. Some organisations and individuals may also permitted or licensed to use vehicles on the beach such as emergency services, beach cleaners and laver weed collectors.

The National Park Authority leases most of the foreshore (the part of the beach between mean high and low tide) along the Pembrokeshire Coast from The Crown Estate. This means that the Authority can control what happens on that stretch of land and cars can be excluded if there is either a physical barrier or a means of enforcing the byelaw if that becomes necessary.

Cars parking on the beach at Newport Sands

Cars parking on the beach at Newport Sands

In a few cases (such as Newport Sands) there is a tradition of parking on the beach which is strongly supported by local people. This can present a big problem for the National Park Authority as it is difficult to manage, with the underlying worry that a child or an adult might be struck by a car and be injured. The Authority purchased the land traditionally used for beach parking in 2023. To find out more visit our ‘Turning the Tide on Beach Parking at Newport Sands’ page.

Climbing at St Govan’s

It is often easy to look for problems and conflicts rather than celebrate where success has been achieved. This case study looking at the issues surrounding climbing at St Govan’s Head is one that demonstrates that with time and effective communication, conflict can be resolved and a relationship built on trust established.

The magnificent limestone cliffs in South West Pembrokeshire are an attraction to all kinds of users. Rare species of bird such as the chough and peregrine falcon find them ideal nestsites, and several species of seabird return to them each year to raise their young. The clefts, hollows and caves are a suitable habitat for bats, especially during the summer months. The cliffs are also appealing to holiday makers and walkers, giving spectacular views. But the cliffs are especially attractive to climbers, attracting visitors from around the world.

Climbing at St Govan’s

Climbing at St Govan’s

A visit to the site during the spring or summer will find many people enjoying the scenery; walkers, families, climbers, birdwatchers. Yet the situation for climbers was not always such a happy one. When the Pembrokeshire Coast Path was created in the early 1970s, access to the cliffs at St Govan’s was restricted. The land was owned by the Ministry of Defence (MOD) and the National Park Authority, among other groups, were concerned that any activity would be damaging to the birdlife of the area.

The solution was to establish a Recording and Advisory Group, begun in 1978. The group initially consisted of the MOD, the National Park Authority, West Wales Wildlife Trust and the British Mountaineering Council, but has grown over time to include other interest groups, including the local climbing club, National Trust and Sports Council for Wales. From the group a leaflet of ‘Agreed Climbing Restrictions’ was produced. This leaflet did not seek to prohibit climbing activity, but to restrict it from certain areas during certain times of the year when birds were nesting. From this beginning further measures have developed.

The extent of climbing has been extended further westwards into the Castlemartin Ranges. Monitoring was introduced of where and when birds were nesting. In this way it has been possible to adapt and refine restrictions.

- A Castlemartin Ranger was appointed. This Ranger not only monitors the ranges with the MOD and National Park Authority, but works closely with climbers. The communication is two-way, and this is important. Climbers can learn about restrictions, and how their movement can affect the birdlife. But equally, the climbers are able to inform the Ranger about where species are nesting, and about potential hazards on the cliffs.

- The introduction of a cliff top marker scheme. This marks where climbing is restricted. The British Mountaineering Council have funded the replacement of markers, working with the MOD. Markers and signs have been adapted at belay points, making it clear where restrictions apply, it having been noticed that once at the bottom of the cliffs the climbers could not see the markers high above.

Thirty years on, and the successes achieved must be celebrated. They are the result of good communication and trust. With an eye on the future, it is now recognised that the growing number of different recreational users at St Govan’s Head needs to be monitored, and the model established by the climbing community, National Park Authority and MOD may be an effective starting point for that.

Footpath Erosion

The Pembrokeshire Coast Path is a major attraction. People access the Coast Path to walk, but they also use the Path to undertake other activities, such as climbing and fishing. The general effect of all these feet is to trample vegetation and to compact the top layer of soil. Over time, a slight groove is formed along the line of the Path. In most cases this is not a problem. The temperate climate of Pembrokeshire and the fertile soils allow for a growing season of nine months, and most paths can recover naturally.

Group of Walkers on St David’s Head

Group of Walkers on St David’s Head

However, sometimes problems do occur:

- At honeypot sites. These are the most popular parts of the Coast Path, and typically occur around car parks, beaches and viewpoints. At the Green Bridge of Wales near Castlemartin the ground has been eroded at the entry to the viewpoint and around the base because people wish to enjoy the view of the natural arch.

- Where the soil is thin it can be worn away to expose the bedrock. This is uncomfortable to walk on. Walkers tend to walk on either side of an affected area, widening the Path, and trampling the vegetation.

- On the Coast Path where there are especially beautiful views from the cliff or access to ledges for fishing. Paths form from the main Trail to the cliff edge. This can be dangerous both in terms of safety and conservation.

- On slopes. Problems occur when the grooves worn by walkers become channels for rainwater.

- At archaeological sites. The Coast Path passes close to and through a number of historic landscapes, including several Iron Age Hill Forts. These interesting sites are vulnerable to destruction by erosion. At St Govan’s Head Medieval field boundaries and growing plots have been eroded from the cliff edge, in part caused by climbing activity.

Where erosion occurs there are a number of solutions:

- Where bedrock is exposed it is possible to cut stone away and create a smooth surface, encouraging walkers to stay on the Path.

- Reintroduction of turf and vegetation to deter people from using side paths. This occurred at Freshwater East where the sand dunes had been heavily eroded over many years. The area, in this instance, was fenced off to allow regeneration. Now re-opened, there is a designated trail through the dunes.

- The cutting of gullies and introduction of deflectors to divert and manage rainwater and run off.

- Fencing off of areas of higher sensitivity such as archaeological sites or areas with rare flora and fauna. Where this occurs the National Park Authority display information to inform Path users.

The National Park Authority manages the Coast Path to maximise access and enjoyment. However, the impact of users has to be balanced against protecting the landscape quality and nature conservation.

Recreation at Porth Clais

Porth Clais is a small tidal inlet on the St David’s Peninsula. The cliffs of sandstone offer opportunities for climbing and fishing, while the small harbour is a safe place from which small vessels, canoes and kayaks may be launched. The coastal landscape is mainly sea cliff heath, but an important habitat for invertebrates and breeding birds such as rock pipits. The heavily indented coast, pitted with caves, makes a good habitat for seals, providing shelter and safety from prying eyes on the cliffs above. The area is owned and managed by the National Trust, who provide a car park and toilets.

On a gloriously sunny June afternoon in 2008 Porth Clais was a veritable honeypot, with an overflowing car park, and lots of visitors enjoying the warmth of the day. In the mile-long walk from the harbour to St Non’s Chapel there were four groups coasteering, two pairs of fishermen fishing from the sandstone ledges, three groups of climbers, two small fishing boats, two groups sailing kayaks and canoes, six groups of walkers, three families picnicking and one family crab catching off the harbour wall.

Porth Clais harbour

Porth Clais harbour

But was that level of recreational use good for that part of the coast? In the same mile-long walk very little wildlife was seen, only a few gulls hovering overhead, eyeing the discarded picnic food. Too many people in one place bring a new set of problems.

These include tension between different users. On that afternoon a walker seeking peace and beautiful views, was competing with excited and lively coasteering youngsters. On the sea below one group in kayaks found themselves in the path of fishing boat, which led to an altercation. It can also lead to the loss of habitat for wildlife. Seals prefer quiet secluded locations, but these were the very places being explored by sailors and coaststeerers.

Erosion is also a problem at popular spots and at Porth Clais it was the access path from the harbour to the cliffs that was being most heavily worn. There is also the issue of litter and a greater demand on infrastructure such as the car parks, toilets, slipway, and narrow country lane to Porth Clais.

The National Park Authority works with local recreational providers, landowners and conservation groups. Codes of conduct are in place, such as the Marine Code and agreed restrictions for climbers, which encourage users to behave thoughtfully and responsibly, and to avoid damage and disturbance. But in this instance were there simply too many people in one place at one time? If so, what should the solution be? It is almost impossible to predict how many people will use one place on a single day. Is the solution to restrict certain activities from certain places? Is that just pushing the problem further along the coast?

What solutions would you suggest? And how would you bring agreement about? These are issues that affect the National Park Authority each year, and which it works hard to manage. But they are issues that need to be solved in partnership with others.