The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park makes up approximately 20% of the Welsh coast. A coastal environment contains any habitat that is influenced by or connected to the sea. The sea influences all of the habitats within the National Park.

Habitats such as rocky shores and sand dunes are affected by the tide, wind and waves. The species that live here have to be able to survive these conditions as well as the saltiness of the water.

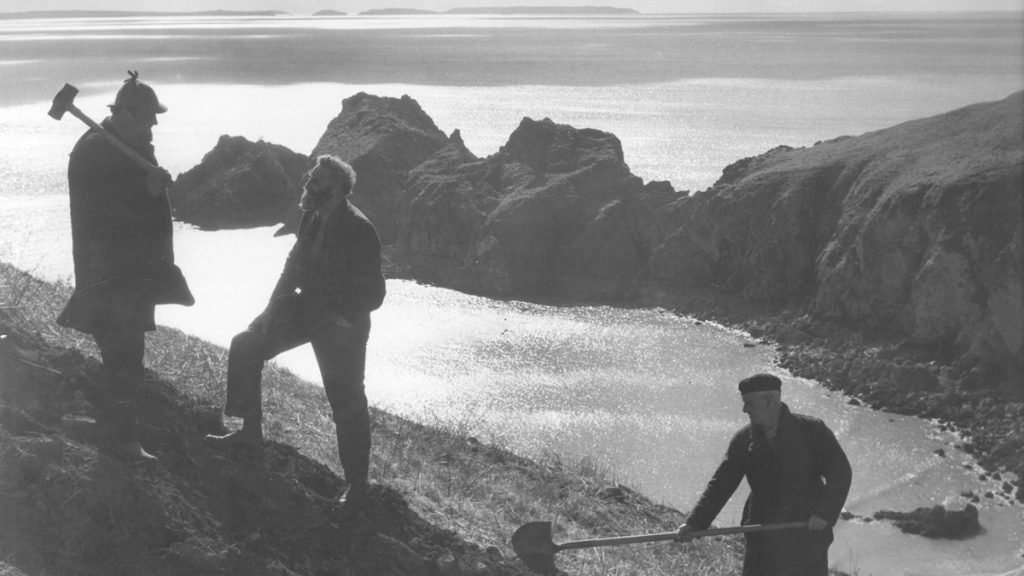

Coastal Slopes

What makes coastal slopes special?

Coastal landscapes are among the most treasured landscapes in the UK. The National Park’s coastal belt covers approximately 4,400 hectares of land area. It consists of two main habitat types: maritime grassland and coastal heath. It’s a long, narrow piece of land, stretching for nearly 260km.

The coastal belt varies in width from just a few metres to extensive plateaus and headlands. It contrasts strongly with the county’s intensively farmed interior. It’s the National Park’s major visitor attraction as is the land surrounding the Pembrokeshire Coast Path National Trail.

How is this habitat threatened?

In the 1980s it was recognised that the coastal belt was beginning to be dominated by scrub species such as gorse, bracken and bramble. These species have changed the landscape from a patchwork of habitats to a monotonous expanse with reduced biodiversity. This transition has come about as a result of the changes in farming since the 1950s. Modern farming techniques have ‘improved’ the land or neglected it. Both of these changes have resulted in a decline in traditional methods of management of coastal slopes.

How are the coastal slopes being conserved and managed?

The aim is to make a mosaic of habitats supporting all kinds of species and increase coastal biodiversity. For example, short grass for chough, scrub for birds, long vegetation for small mammals and the boundaries between for invertebrates. The old way of farming these kinds of areas was to use them for grazing land, with the farmers removing gorse and scrub either using fire or by cutting, to keep the area open.

Assistance has been given to farmers to help them to return to more traditional methods of farming. In some areas, assistance has meant the reintroduction of coastal management techniques funded by agri-environmental schemes. The problem of confidence in the old techniques has been tackled by giving farmers help to relearn lost skills.

Islands

There are six main islands off the coast of Pembrokeshire, and all of them are in the National Park. Five of these islands have been inhabited at some point in their history.

In the past, all but Grassholm were used for agricultural uses. The farming was mainly subsistence, but the people who lived on these remote places also exploited the seabirds who made the islands their home. Rabbits were also farmed on the islands, and the legacy of this can been seen on Skomer and Skokholm today.

You learn more about these islands in the Things to Do section.

Rocky Shores

What makes rocky shores special?

Rocky shores are probably the most visited habitat in the National Park as they are part of the beaches most people visit. They make up the shore between the land and the sea where rockpools are visible at low tide. If you have ever poked about in a rockpool then you have been on a rocky shore.

Our shores are largely free from pollution and major disturbance, so the organisms that live here are diverse and fascinating. Many of these shores are very exposed to wave action because they face west or south-west, which is the prevailing wind direction. As a result they are very diverse.

Many of the organisms found here are unique. It has been suggested that the diversity of creatures from low to high tide on Pembrokeshire shores is the same as the diversity from the equator to the North Pole! The organisms at the top of the shore get much less water than those at the bottom because of the tide rising and falling. The amount of exposure to the air gives rise to a repeated pattern of zones that’s common to all shores:

Splash zone

The zone above high tide. It is splashed but not covered by the sea. It is a dry, salty place where orange, black and grey lichen survive. Specially adapted plants such as sea thrift and sea campion can live here. These plants are known as halophytes.

Upper zone

This zone is covered by sea between 1% and 20% of the time. It is distinguished by bright green seaweed.

Middle shore

This is an area that gets covered by the sea between 20% and 80% of the time. It looks brown because of the brown seaweed species commonly known as wracks, such as bladder wrack and spiral wrack. It turns grey as you get lower down it, as the rocks become encrusted with barnacles, limpets and whelks.

Lower shore

The area that is covered for between 80% and 99% of the time. This area looks red because of red seaweeds like dulse and catanella. In some pools there can be up to 11 different species of red seaweed.

The organisms that live in this ever-changing place must be able to survive the waves and potentially being dried out twice a day. Adaptations to wave action include strong hold-fasts to the rock, as seen on seaweed, and encrusting as seen in barnacles and sponges. Limpets have a cone shape to resist the force of the waves. Other shellfish cling to the rocks with a very strong sucking action. Other creatures like crabs and starfish hide under rocks to keep out of the swell.

To survive drying out, animals can hide in their protective shells. Seaweeds are tough and rubbery so can survive a certain amount of drying out. At low tide, pools of water are left in dips and crevices in the rock. These rockpools are holding bays for creatures that have been trapped by the falling tide. Here you might find crabs hiding under the seaweed, or even a fish or prawns swimming and grazing on the algae. Sea anemones such the gem and beadlet anemone also like to be in rockpools so they can feed between low and high water. If they do get uncovered their bodies are protected in a jelly-like blob.

How is this habitat threatened?

Rocky shore creatures do not need any specific management to conserve them but can be at risk if people take creatures or plants away or erode them by walking. They are very sensitive to pollution such as agricultural chemicals or oil spills from pleasure boats and oil tankers.

The biggest threat is probably sea temperature change, as an increase in sea temperature increases algal blooms, reducing the oxygen levels and reducing the survival rate of many species found on our shores. If global warming continues then the biodiversity of our rocky shores will change and may be reduced.

Sand Dunes

What makes sand dunes important?

Sand dunes are hills of sand that can only occur on the coast, where there is enough sand exposed at low tide to dry out and be blown inland. The sand is heaped up by the wind into mounds when the blown grains hit an obstacle. Over time, dune-building plants, which trap the sand and stabilise its movement, cover these mounds. Even with plant cover, dunes are ever changing, dynamic habitats. Dunes form on exposed shores, most frequently in bays.

There are 16 sand dune sites in the National Park, about 14% of the UK’s dune systems. They are considered to be so important that 70% of these are protected within conservation sites.

Sand dunes develop and change over time and as they change, so too does their biodiversity. The plants that colonise them are highly specialised to survive such dry, dynamic conditions and are not found in any other habitat.

Sand dunes build through time, in a sequence of forms from flat beach to high hills. The progress of these forms is called succession. The whole process is called dune building.

The start of the dune building is known as the embryo dune stage. Sand trapped by an obstruction builds up until it is unstable and collapses. Plants like marram grass can survive in such unstable conditions, as they don’t need soil to grow in and spread easily if buried by the sand.

When the sand becomes more stable marram grass and other specialist species like sand couch grass, sea holly, and sea spurge take over. This is known as the yellow dune stage. The mounds are still low and there is more sand uncovered than covered.

Finally the sand becomes fixed into place and organic matter builds up. The dune no longer looks yellow and sandy but is covered with vegetation. This stage is known as a grey dune. The dune now has its greatest plant biodiversity. The types of plants growing here depend on whether the sand is made of shell fragments or of mineral grains. Shell sand makes for an alkaline grey dune with alkaline loving plants like creeping willow, silver weed and creeping bent grass, growing on it.

Sand derived from mineral grains makes an acid grey dune with acid loving plants like heather, bell heather, sand sedge, lichens and mosses growing on it. The acid heath of a sand dune is a very threatened habitat because it is easily destroyed by trampling and can be improved by farmers to make grazing pasture or by golf clubs to make greens.

How is this habitat threatened?

Dunes are dynamic places because of the nature of shifting sand but several factors seem to result in a net decline of this habitat and its erosion. Erosion means too little sand in the system to keep them stable.

Sand can be removed wholesale by destructive storms or by humans. People have used the sand for construction in the past but this practice is now illegal. Humans do use dunes for recreation, which damages the plants and so stops the dune development. Just walking through the dunes can damage them beyond survival. Dunes can also make good golf courses, which artificially create greens and fairways and stop the natural movement of the sand.

Sea defences can also prevent the natural movement of the sand because they remove the source of the sand out at sea and stop it entering the dune system. Invasion of non-native plants like sea buckthorn can change the biodiversity of the grey dune. Lack of grazing by rabbits allows the soft heathland grasses to be taken over by rough grasses and then develop into scrub.

What action is being taken to conserve sand dunes?

The dunes that are within SSSI sites are monitored to assess if any changes occur. Other sites are monitored and surveyed by conservation groups like the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales. Liaison between interested groups like Tenby Golf Club and the National Park Rangers increases awareness of the habitat and provides advice about its maintenance on dunes popular with the public.