As the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park is surrounded by the sea on three sides, its climate, even in the more inland areas, has a strong maritime influence.

Inland environments are kept warmer in winter (and cooler in summer) by the North Atlantic Drift (a warm sea current) and kept moist by the prevailing south-westerly winds off the North Atlantic Ocean.

Most farmland in Pembrokeshire is of good quality and has been intensively farmed for dairy, beef, arable or early potatoes and this pattern continues. However, some parts such as hedgerows, woodlands, and marshy or scrubby areas of poorer or thinner soils, steep slopes and narrow stream valleys.

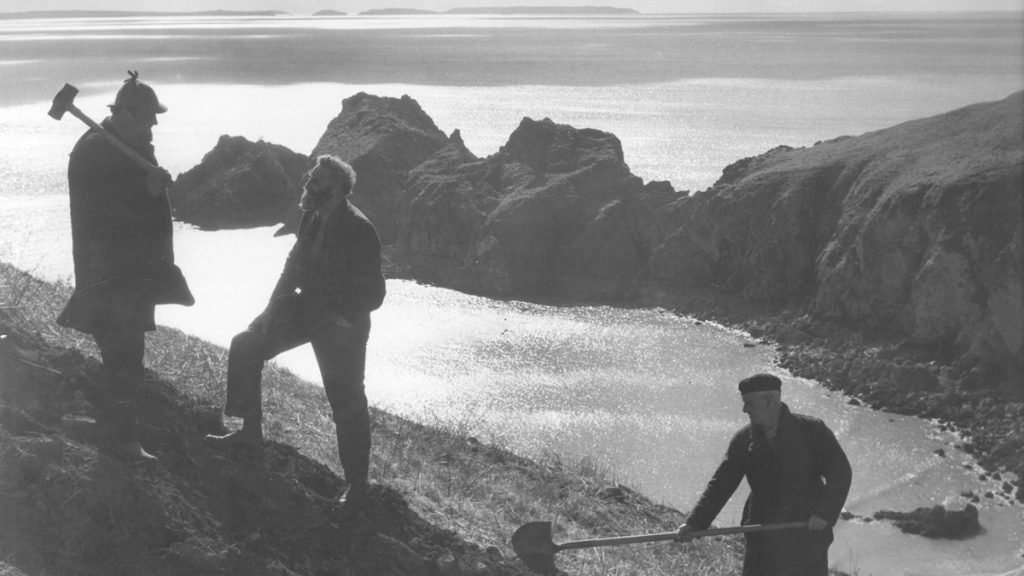

During World War II some of this poor marginal land, such as scrub, marshy land and the edges of fields, was brought into cultivation to grow more food and help the war effort. This meant that more land was being farmed and so there was less land area for wildlife in the form of wilder, uncultivated habitats.

Even under wartime pressures, some pieces of land in the most inaccessible parts of farms could not be farmed. These included steep and stoney slopes and deep narrow valleys. These areas became havens for wildlife, as there was least disturbance and species diversity.

After the war, the marginal land was allowed to revert to its natural state as it was no longer needed or wanted for food production.

It is the wilder and more natural parts of each farm that provide homes for the greatest variety of wild creatures and plants. These inland habitats need careful management to maintain their diversity. Some of the habitats contain rare species that need our protection to survive and thrive.

Conservation management of specific habitats will also help to increase the overall biodiversity of the National Park.

Mudflats and Estuaries

Why are these places important?

Mudflats and estuaries look like unpromising, dirty habitats, but in fact their biological production is the same as that of the tropical rainforest. Their biodiversity is vast and so they are very important features in the National Park.

They were formed by the flooding of river valleys after the last Ice Age. The mud has been building up for 8,000 years. The largest estuary is the Daugleddau. It is fed by the Eastern and Western Cleddau rivers from upstream, and broadens into the Milford Haven Waterway – one of the largest natural harbours in the world – downstream. This waterway is so important it is designated a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and it is a Wildfowl Sanctuary. This means birds can’t be shot in this area. It is especially important for the conservation of otters and less well-known species such as lamprey fish. Estuaries are important staging posts for migrating birds in the winter because the water and mud is full of high-energy food, such as worms and shellfish.

What are the characteristics of estuaries?

The mudflats are formed by the perfect balance of the rivers dropping their sediment and the erosion caused by gentle wave action from the rise and fall of the tide. They are constantly being washed with new saltwater as the tide rises. The saltwater is diluted by the constant flow of river water in the area. Plants and animals that live here must be able to cope with such dynamically changing conditions. These plants and animals are called Halophytes, which means they can live in a salty environment. The animals are adapted to hide when the tide goes out, either directly under rocks or by burrowing into the mud. For example, sand hoppers swim in the brackish (half salt, half fresh) water, and then hide under rocks at low tide. Worms such as lugworm, and bivalves such as cockles come to the surface only when the tide is in.

Plants are adapted in the same ways that desert plants are adapted to the dry environment. Sea purslane has silver-scaled, fleshy leaves. The fleshiness conserves water and the scales that protect the leaf make it appear silver. Glasswort is a succulent plant that was used to make the soda ash needed for glassmaking. These two species grow on the mud, making a salt marsh. They are the first or ‘pioneer’ species that allow the salt marsh to change gradually over time.

The plants play an important role in building up the sediment until the soil is deep enough to support trees. This process is called succession. The mud is gradually stabilised by the roots of the pioneer plants, sea purslane and glasswort, allowing cord grass or rice grass to grow. Next grow the rushes, such as hard rush and saltmarsh rush, and sedges including brown sedge, followed by shrubs such as gorse and willow. As the vegetation changes, so too do the animals – they change from marine to land-living, such as otter to fox.

What are the threats to this habitat?

Mudflats are very sensitive to physical and chemical damage. Trampling on the soft mud can destroy its delicate structure. The wash of waves from speeding boats can also damage the mud’s structure.

Fertiliser from improved fields can be carried into the water and change the chemical balance of the mud, affecting the survival of organisms living there. Oil pollution from boats can spread over the mud and sink into it at low tide, also harming the organisms.

Bait digging too can cause huge damage because it can reduce the population of some worm species; it also destroys the habitat of the mud by destroying its structure.

Heathland

What are Heathlands?

Heathlands are areas of dwarf shrubs, such as common heather (ling), bell heather, cross-leaved heather and western gorse. These plants grow well on nutrient-poor soil. This type of vegetation is characteristic of the coastal peninsulas of St Davids and Strumble Head and also large areas of inland moor. There is more lowland heath in Pembrokeshire than anywhere else in Wales. Heaths vary because the plants that grow in them are subtly different because of the soil type and moisture content.

What makes them special and why are they under threat?

Heathland looks like a natural and wild habitat but is the result of forest clearance for agriculture around 5,000 years ago. The farmers used repeated cycles of grazing and burning, creating the large tracts of heathland we see today.

Over the last 100 years large tracts of heathland have been lost because of changes in farming methods and land improvement, such as using fertilisers. What remains is threatened by neglect. Most of the inland heaths that have been lost were very wet and looked like marshy grassland with willow scrub. These areas have been improved by drainage to make rough pasture. Improvement of such areas does not create valuable grassland for grazing but has encouraged the loss of traditional farming practices such as burning, grazing by a range of animals, cutting and clay digging.

More importantly, it is the very wetness of these places that helps create such a valuable and varied habitat. They are especially good at supporting a rich variety of insects, such as the rare southern damselfly, the marshland fritillary butterfly, green tiger beetle and the emperor moth caterpillar. The specific nature of the heath they live on determines the survival of these species. For example, the devil’s-bit scabious is the food plant of the marsh fritillary caterpillar, and it grows well in wet heath. Only by reintroducing old farming practices can heathland remain a living part of Pembrokeshire.

How are these areas being protected?

Penlan Forest case study

The heathland at Penlan Forest had been hidden by a Sitka spruce plantation since 1970. Even as a monoculture, 30% of the plantation remained as heath. Now it is owned by the National Park Authority it is being recreated to blend the heath into the habitat of oak woodland in the Gwaun Valley below, making a heath/woodland mosaic. As the spruce trees were being felled it was found there were enough heathland species seeds below the needles to recreate the habitat naturally. The oak woodland is being replanted using sapling trees. Care is being taken in both habitats to control the spruce seedlings. The project has been under way for five years and the results are promising.

St Davids Airfield case study

Recreation of the wet heathland at St Davids Airfield began by the removal of all the old buildings, then the replacement of the topsoil with natural clay. Then turfs with appropriate plant types were transplanted into the specific areas and the space between was covered with brash from cuttings of mature heathland. This brash carries the seeds of heather and gorse, which naturally germinate in the area. These areas are now burned on a five-year cycle and grazed in the winter by a mix of sheep and cattle.

There is a restored organic meadow within the airfield. In this area the grass is cut for hay once a season in July so wildflowers can set seed. No chemicals are used to improve its growth. The project has been a success, both for the heath and the meadow habitats, because the biodiversity of both habitats is increasing year on year.

Dowrog Common case study

Dowrog Common near St Davids has been under restoration for the past 30 years. It has been restored by the removal of invasive species such as bracken, scrub and rhododendrons. Up until 1990 this was done by burning every winter. Since 1990 grazing has been the management technique. The result of this long period of management is stable populations of some rare species, such as the slender yellow centaury, pale dog violet, cladonia pezizformis lichen and red damselflies and a rich variety of heathland mosaic habitats.

Waterways

What is a waterway?

A waterway is any passage of fresh water of a river or stream, from the land to the sea. Waterways are special because they are tranquil places were you can walk and watch the wildlife or enjoy sports such as fishing or canoeing. They are dynamic habitats because the water moves through them and changes the land as it flows. In the Park, waterways are not much changed by man, resulting in a rich habitat that is home to such species as otters, kingfishers, dippers and bats. These species only live in or near unpolluted, undisturbed water.

Why are waterways so important?

Waterways are important because they link habitats together and provide rich and varied food sources – just like supermarkets! Insects are one of the ‘superfoods’ found here.

Waterways are a ‘mosaic’ habitat divided into four areas: aquatic, marginal, bank edge and valley. Each habitat has its own organisms living in it, such as aquatic plants like yellow flag iris, insects – including dragonflies – that live in the river bottom as a nymph and fly above as an adult, and mammals such as the otter which hunt in the water and live in the banks. A good freshwater habitat has to have clear, pollution-free water.

The inland area of the Park is covered with rivers and streams that vary in size and type. The largest catchment areas are the Eastern and Western Cleddau, the Daugleddau and Milford Haven Waterway. Smaller catchments include those of the Nevern, Gwaun, Solva, Alun and Ritec rivers. All protection and monitoring of these rivers as a water resource is carried out by the Natural Resources Wales, but the National Park Authority has a duty to protect and maintain the high levels of water quality and to protect species living there. All the waterways are classified as River Ecosystem Class 1 and 2. This means they are of good or very good water quality for all fish species, ie clear and unpolluted.

How are waterways threatened?

There are several ways a watercourse can be damaged and the habitat quality reduced:

- Pollution by sewage and industrial outfall has reduced significantly in the past 30 years. However ‘diffuse’ pollution is becoming more of an issue. This is when chemicals used by farmers, eg sheep dip or fertiliser, slowly move through the soil and into the water, causing direct damage to the organisms or damaging the water quality by the process of Eutrophication. Run-off from roads also adds to the amount of diffuse pollution, especially from salting in the winter.

- Abstraction means the removal of water eg for use by humans or by drought. If too much water is abstracted the pollutants get concentrated and oxygen levels are lowered. Both can harm organisms living in the water.

- Changes in how a river flows naturally, by stabilising banks or digging pools, can affect the balance of the habitat and cause it to change. If this results in damage, it is usually shown as reduced biodiversity for an affected area.

- Siltation occurs if water runs off fields or areas of bare soil, because tiny particles of soil can be carried in the water and can cause injuries or even suffocation to fish in the waterway. It can also damage spawning beds and riverbed invertebrates. To prevent this it is best to have an area of vegetation between the bare soil and the water. This is called a buffer zone.

- Invasive non-native species can invade and spread along a waterway, out-competing the native plants and reducing the biodiversity to a monoculture. Examples of these alien plants are Japanese knotweed, New Zealand stonecrop, water fern and Himalayan balsam. To prevent damage to the habitat, these plants must be controlled by spraying them with weed killer.

How are waterways protected?

There are two key areas where the National Park Authority has an influence:

- In the promotion of more sustainable water use, by using its planning controls to make sure water use is not unnecessary or harmful to the habitat.

- By liaising and working with farmers to help them to use water in ways appropriate to the habitat and thus to reduce direct pollution.

Woodlands

What is a woodland?

A woodland habitat is a mix of layers of tree species and shrubs, from the top canopy down to the ground. There are three layers to a wood. The top layer (canopy) is the large tree layer, in Pembrokeshire this is often the sessile oak. The middle layer has smaller trees such as rowan, hazel and holly, and shrubs like bramble. Ivy and honeysuckle grow through the middle layer acting as a bridge between the ground and the canopy. Finally, there are the ground storey plants such as bluebell, ferns, wood anemone, wood sorrel and violets.

There are two kinds of woodland found in Pembrokeshire: lowland oak woodland and ash groves. The most common kind is the lowland oak woodland, where the dominant tree species is sessile oak. This type of habitat is typical of mild maritime climates. The best examples of semi-natural oak woodland are in the Gwaun and Nevern valleys and in the Upper Daugleddau. Ash groves exist only in base-rich soils in the south of the county.

The mild, damp conditions make a good environment for lichen species. In some of the Gwaun woods there are 750 different types of lichen growing on trees and on the woodland floor. There is also a wide variety of ferns, some common and some scarce, such as the rare filmy ferns and the hay-scented buckler fern.

How is this habitat being protected?

The protection and expansion of woodland in Pembrokeshire is a high priority for the National Park Authority and its partner organisations.

Woodland covers only about 6% of Pembrokeshire, in a very patchy fashion. Where it exists, it is found on the edges of farmland. Before 1600 about 30% of land was woodland, so as a habitat it has been declining for at least 400 years. In the past 100 years, loss has mainly been due to the planting of conifer plantations.

Since World War I, woodland management has declined because the skills of this kind of management have been lost. Also non-native species have been introduced and are invading large areas of woodland.

The long-term aim is to restore the neglected areas and expand the coverage though planting schemes. Any new trees planted have to be native and suitable for a Pembrokeshire woodland, so old conifer plantations, for example at Penlan Forest, are replanted with natives. There is also control of non-native species, such as sycamore and beech, so they make up less than 10% of the canopy. In the under-storey there is control of non-native weeds like Japanese knotweed, laurel and rhododendron. The neglected woods are properly managed to remove dead wood as appropriate so natural regeneration can take place. Trees are felled to make the age structure better; that is 10% of the wood is trees less than 20 years old and 10% mature trees, with shrubs left to age.

These improvements can only be achieved by the National Park Authority working with other interested bodies such as the Forestry Commission, Natural Resources Wales and the Wildlife Trust South and West Wales.

The Authority employs a Tree and Landscape Officer, who works with the Development Management team as trees are an integral feature of the landscape and require particular attention when considering a planning application, as well as general tree and hedge management. The Authority also runs a Woodland Centre at Cilrhedyn near Fishguard, which produces various wooden products, including signposts, stiles and benches.