A visit to a sea bird colony is a true assault on the senses; the movement, sounds and smells of thousands of birds filling the air and the cliff ledges. But for much of the year the same cliffs that bustled during the spring and early summer are strangely empty and silent places.

Several species of sea bird use the islands and cliffs of the Pembrokeshire coast as places to breed; to lay eggs and raise young. These birds spend almost their entire lives on the sea or wing, but cannot divorce themselves entirely from land, needing a dry and secure place to raise the next generation. For them, the sheer cliffs and remote islands offer sanctuary from predators and security from the rigours of the sea.

Some of the sea birds that choose Pembrokeshire to raise their young have travelled incredible distances. Manx shearwaters come from South America, while puffins may come from as far as North Africa or Canada. Others, such as the guillemot and the razorbill live in the Irish Sea all year, but come ashore to breed.

Guillemots and Razorbills

Among the many sea bird visitors to Pembrokeshire who come to these shores to breed are two members of the auk family, the guillemot and razorbill. While they can be seen breeding on the offshore islands such as Skomer or Ramsey, it is also possible to get close views of these birds from the mainland.

Looking rather like penguins, razorbills and guillemots stand upright on cliff ledges. The guillemot is a chocolate brown bird, with a white tummy and a sharp dagger like beak. In contrast, the razorbill is a black bird, again with a white tummy. The razorbill has a white stripe across its beak and eyes, looking almost like a comedy thief’s mask. The beak is stubbier. Both birds nest on cliffs. The guillemots prefer to pack together, standing shoulder to shoulder on narrow ledges, while razorbills prefer clefts in the rock, or flatter wider outcrops.

Breeding on a narrow edge could be considered a risky business but the egg of the guillemot has evolved to be pointed, so that it will roll in a circle from the point, but not off the cliff edge. Both razorbills and guillemots, like many seabirds, raise a single chick, breeding from May to early July. They are among the first birds to fledge from the cliffs, and are gone before the puffins leave their cliff top burrows.

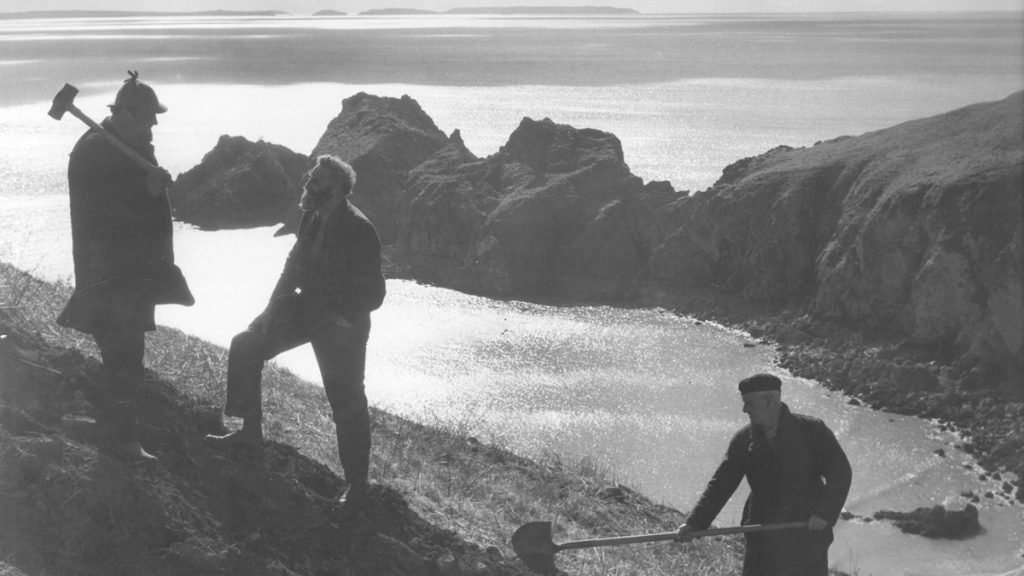

Razorbills and guillemots can be seen from the mainland along the Castlemartin coast across to Stackpole. One of the best views is at Stack Rocks, close to the Green Bridge of Wales. This is one of the largest guillemot breeding sites in South Wales. Along the coast at Flimston razorbills and guillemots breed in the sea caves, along with the kittiwake, a small member of the gull family.

Puffins

Ask the majority of visitors to Skomer Island what it is they want to see and the answer is almost certainly puffins. These delightful birds with their brightly coloured bills are part of the largest colony of puffins in Southern Britain. Each year around 6,000 of them return to spend the spring and summer on Skomer.

Puffins arrive on Skomer in late March, but don’t immediately settle down on the island. Initially they collect in rafts at sea, as if to build up their confidence to storm the island. But soon they return to the cliff tops to re-occupy burrows where they will lay a single egg which will hatch in June. After, the birds can be seen flying into the island, with beaks lined with sand eels. By late July the birds depart the island and return to a life at sea. It is then that the brightly coloured bills, for which puffins are so recognisable, fade, to come to life again next spring.

Many people are surprised when they first see a puffin by how small they are, just 30cm from beak to tail. They also marvel at how relaxed they seem around visitors to the island, crossing the paths to reach their burrows, while navigating their way through feet and legs. The best time to see puffins on Skomer Island is between May and early July.

Manx shearwaters

It is hard to believe that Skomer Island supports the world’s largest breeding colony of the Manx shearwater, a cousin of the wandering albatross. Certainly a visitor to Skomer during daytime would see almost no evidence of the 120,000 pairs of birds raising their chicks on the island.

The reason for this is that, like the puffin, the Manx shearwater nests in burrows. But unlike the puffin, the shearwater only leaves and returns to Skomer under the cover of darkness. These small white and black birds are almost entirely designed for life on the wing, with legs that are small and tucked far back under their bodies. On land they move awkwardly, and are easy pickings for the gulls that live on Skomer. To avoid them, shearwaters return to their burrows at night calling to their mates and chicks below ground. This call is quite unique, and once heard never forgotten.

Shearwaters return to Skomer in early spring, and lay a single egg in late May. The chicks hatch after 51 days, and take a further 70 days to fledge, one of the longest breeding periods of any of the seabirds on Skomer. Fledging occurs in September and October, but surprisingly for a bird destined to fly to the South Atlantic, the parents do not guide their chicks. Instead, the adults depart Skomer before the young, leaving the chicks to survive on fat reserves. How these young shearwaters make such a huge journey is a marvel of nature.

For a chance to see shearwaters the National Park Authority offers shearwater walks during the summer. These mainland walks offer views of the adult birds resting and feeding offshore. See Coast to Coast for more details.